Transfer to sea

3.3% of the wastage in fish farming today can be attributed to the fact that the fish cannot tolerate the transition from freshwater to seawater.

The transfer represents a substantial change in the surroundings of the fish, that must go from living in an environment where there is good control over what is in the water it lives in, to an environment with undreamed of quantities of infection agents and environmental influences.

In addition, the fish must completely rebuild its physiology from being adapted to living in freshwater to being a saltwater fish. This requires adaptations throughout the juvenile fish phase, and a precise calculation of the correct exposure time to ensure the best possible transition for the fish.

Facts

From nature's perspective, salmonids are adapted to living parts of their life in freshwater, and parts of their life in saltwater. In the wild, they begin their lives in rivers, and live there until smoltification has been completed, when they migrate out to sea where they stay until they reproduce. They then return to the rivers where they grow up to spawn.

In a fish farm situation, we simulate this life cycle by keeping the fish in freshwater in hatcheries and then transfer them to seawater facilities. We do this within a considerably shorter period than in nature, and there is therefore a short period when it is the perfect time to transfer the fish to the sea. We call this period the "smolt window". If this smolt window is missed, the fish will have problems with adapting to their new environment.

If the fish have been exposed to health problems in the juvenile fish phase, they can be poorly equipped to deal with the transition to the sea. For this reason, the operating conditions in the juvenile fish phase have also been important for those who operate fish farms in the saltwater phase.

Smoltification

The process whereby the fish go from being adapted to a life in freshwater to being in seawater.

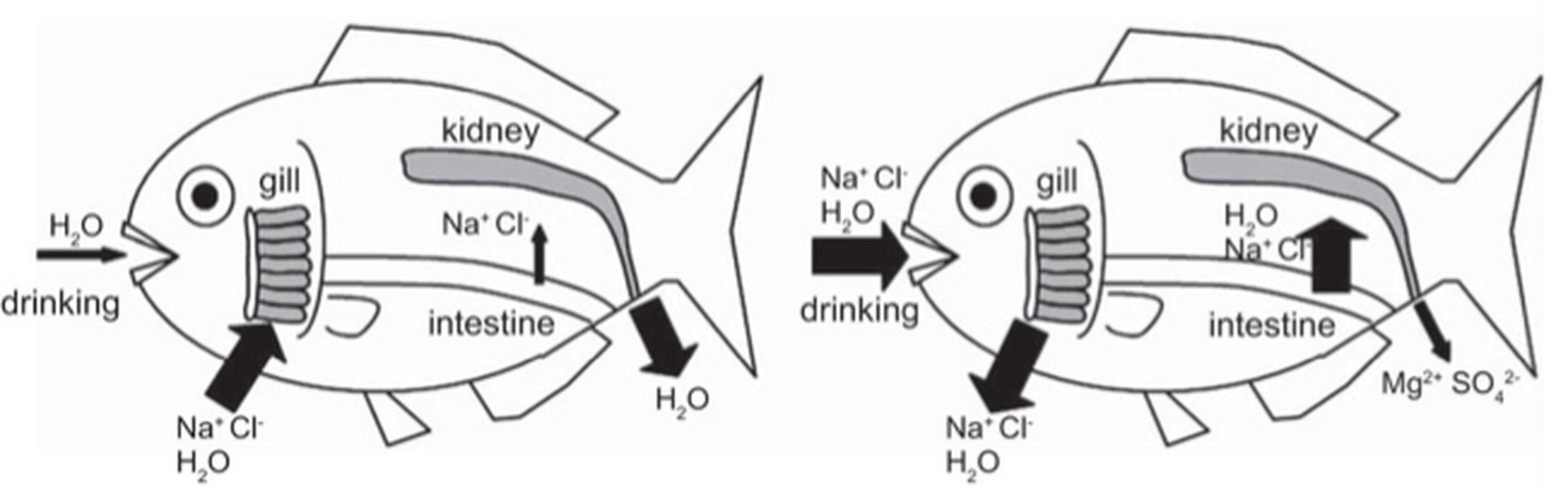

In freshwater, the inside of the fish will be saltier than the surroundings. This means that water is being forced into the fish all the time, and to maintain its fluid balance, the fish must excrete water via diluted urine, and gather as much salt as possible from the surroundings via pumps in the gills, and from feed via the intestines

In saltwater, the inside of the fish will be less salty than the surroundings. This means that water is constantly seeping out the fish and it is in danger of dehydrating. This means that the fish must drink large quantities of water and excrete concentrated urine. It also actively excretes salts through the gills via the NA/K and chloride channels in the gills. It is the activity in this respect that we measure when we check whether the fish is ready to be put out to sea.

The fish's water balance

The significance of intestinal health in connection with exposure

The intestine is a key organ in fish health and defence against disease. In addition to being dependent on well-functioning mucous membranes for optimum nutrient intake, the intestine is also important in regulation the fluid balance.

The intestinal wall contains small openings between the intestinal cells, and these are called "tight junctions". In freshwater, these ensure that the fish can take in as much salt as possible from the feed.

In seawater however, these openings are a disadvantage for the fish, in connection with both regulating the fluid balance and in that they represent a point of entry for infection agents. For this reason, closing these channels is probably an important part of the smoltification process.

A well-functioning intestine will be key to both the nutritional status, fluid balalnce and resistance to disease for the fish in the period surrounding its transfer to the sea.

HSS – Haemorrhagic Smolt Syndrome:

Haemorrhagic smolt syndrome is a problem with unclear causes that

occurs in juvenile fish around the time of smoltification. The disease leads to bleeding and subsequent anaemia, and has several similarities with some serious viral diseases. However, no infection agents have been found that can be related to the disease, and it is assumed to be non-infectious.

Symptoms and diagnosis:

Fish suffering from HSS fool around on the surface of the water, and often have bulging eyes, a distended abdomen and pale gills. Some report that the fish acquire a "greenish tint". When an autopsy is performed, you can see bleeding points on the organs, in the fatty tissue and in the muscles, and with the help of microscopy you can see bleeding in the kidneys, heart and fatty tissue. The bleeding in the kidneys will often be the most prominent finding.

Prevention and treatment:

No clear causes for HSS have been discovered, but it is assumed that it is a lack of physiological adaptation that leads to the symptoms. Prevention will therefore be based on assisting the fish to be as healthy as possible throughout the juvenile fish phase.

HSS is often seen in association with production of large smolt. Adding seawater and salt to the feed are methods that have often been used to counteract HSS in such cases.